Months ago, we started working on our pitch deck to express our vision, define our business model, and fund our company. It looks great and tells a compelling story. So, I’ve included select slides here.

Months ago, we started working on our pitch deck to express our vision, define our business model, and fund our company. It looks great and tells a compelling story. So, I’ve included select slides here.

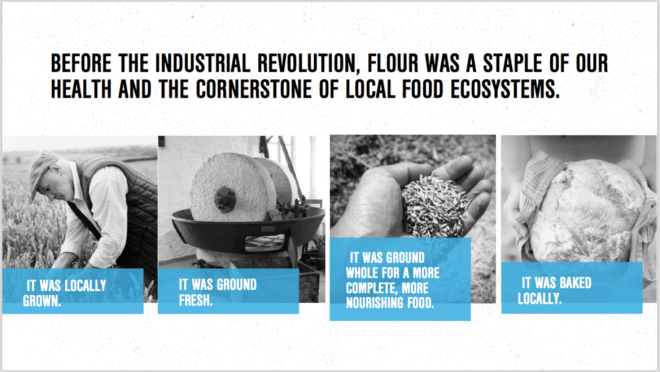

In a nutshell, our deck starts by explaining the way it was — back when flour was a staple of our health and the cornerstone of healthy local food systems.

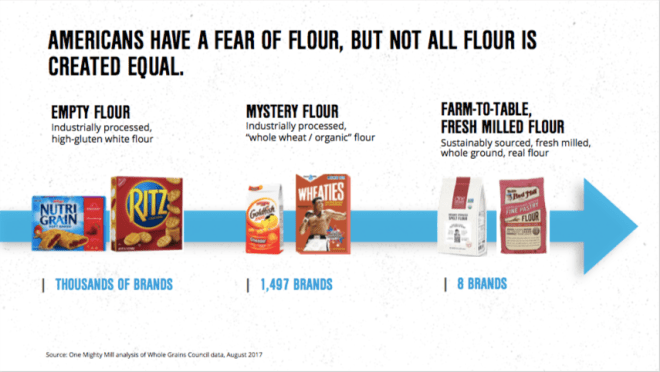

Then, we explain how industrialization and consolidation created wheat and flour that’s empty in nutrition, taste and soul. From there, we dig into the category and market opportunity with data that indicates there’s a massive opportunity for a company to build a brand around a local supply chain and by milling fresh flour.

Next, we introduce our products, packaging, and vision for new product extensions into categories like pasta, cereal and crackers. Our go-to-market strategy is all about winning shelf-space at Whole Foods and building mills in their eastern markets. Finally, we end it with our pro-forma to present the business’ financial viability with some detailed economics.

It took us weeks to complete the deck. And since the first presentation, it’s been a fluid, work in progress that’s been improved by feedback in our meetings.

At this point, I’ve been pitching it for about a month to raise the money required to build the mill and start the business. At the start, you’re completely fired up to finally be able to present the dream. And while it’s been weeks of basically saying the same thing over and over, I do think I’m energized in every meeting. We’ve got something important to say and it comes from a real place. So, I think the passion is clear when I’m presenting.

Anyway, we kicked it off with a few of the most prestigious VC firms in Boston. We don’t want institutional money. But, we did want their feedback and validation. Specifically, we wanted to hear from the smartest people in food and to test our plan with some of the harshest critics.

Since then, I’ve pitched everywhere: on the phone, in big offices, in people’s living rooms after their kids went to bed, in countless coffee shops etc. I’ve pitched all over NYC, Boston, Maine, and the places in between. (One cool highlight was presenting to Gary Vaynerchuck’s team in NY. He’s a legendary entrepreneur and social media mogul.)

The whole process has been reaffirming. I’m certain that our idea is right and opportunity is big. I’m also confident that we can raise the capital we need to do it.

Most importantly, it has reaffirmed what I wanted to do from the start — build a team of people who believe in the same thing. So, the partners who’ll invest in One Mighty Mill will all be playing the long game. They’ll believe in the shared commitment to build an enduring, special company that makes a difference and makes us proud. Founders get worried about control. The fundraising process reminded me that ultimate control is having a team of people who care about the same thing and trust each other to do what’s right.