This weekend, we made these.

This weekend, we made these.

We got wheat berries grown in Maine, ground them on a stone mill in Vermont, rolled the flour out by hand into bagels, and boiled and baked them in Boston. (We just rented commercial kitchen space where we’ll be baking every Wednesday and Saturday morning through the spring.)

We screwed up a bunch of times. (Personally, I have no idea what I’m doing. I basically just wait for instruction and try my best not to form everything I touch into weird shapes). We worked pretty inefficiently. It took 4 hours to make 12 bagels and 12 pretzels. But, it was a big step.

But, it was a big step.

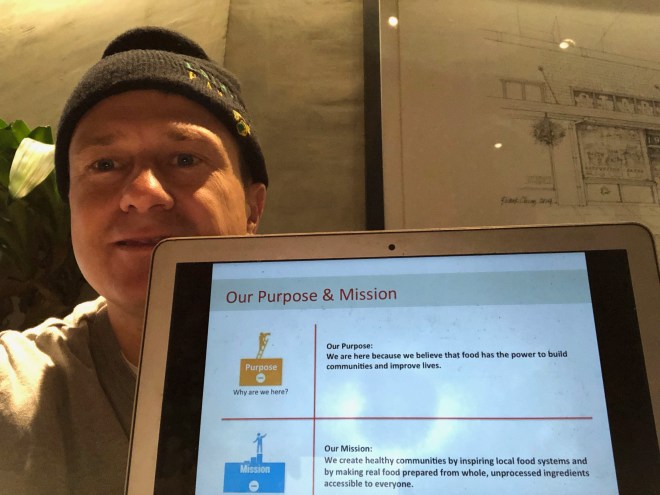

So far, I’ve blogged about everything except our products. Before explaining how we selected them, I need to clarify. Our big idea is making “wheat you can eat”. So, the dream is that One Mighty Mill will be a food brand with a diverse portfolio of products sold at grocery stores. Our flour is the foundation of it all. It’s the critical ingredient that’ll enable the fulfillment of our purpose – to make wheat you can eat by restoring a healthy, local food system. But, we’re not out to sell flour or bake mixes. We want to create a powerful consumer brand that inspires people. And no matter how much value stone milling and local sourcing adds, flour will always be converted into foods made by its customers. That dilutes the connection. So, we want to create that moment of happiness when somebody eats a product that we create by milling local wheat and baking it into something delicious.

Our plan is to launch One Mighty Mill with 3 products: bagels, tortillas (or wraps) and pretzels. We validated the opportunity for each by conducting deep analysis of the “whole grain” products currently sold at America’s grocery stores.

We learned that there are 7,000 “whole grain” products across 18 categories. And in all but a few, there’s serious competition. So, in cereals, sandwich breads, and crackers, it’d be difficult to win consumer attention and grocer shelf space. (It’s crazy – there are more 1,200 cereals alone classified as “whole-grain”!) But, there are hardly any brands competing in the bagel, tortilla (or wrap), and pretzel categories. (In contrast to cereal, there are only 11 pretzel, 23 wrap and 27 bagel brands.) Even more, they haven’t innovated. No bagel, pretzel or tortilla brand conveys their value through nutrition, farm-to-table sourcing, or fresh milling.

As icing on the cake, the 3 products also all have rich history in our food culture. Since restoring local food systems includes reviving and honoring food traditions, products with authentic heritage (i.e. products like bagels, pretzels, and tortillas) strengthen our concept and brand.

Anyway, that’s how we ended up baking those beautiful bagels and pretzels this week for the first time.

We’ll do it again every Wednesday and Saturday morning from here out.

That’s Chris. He started a big digital marketing agency in Boston. We met a few years ago when his firm designed a mobile app for my last company.

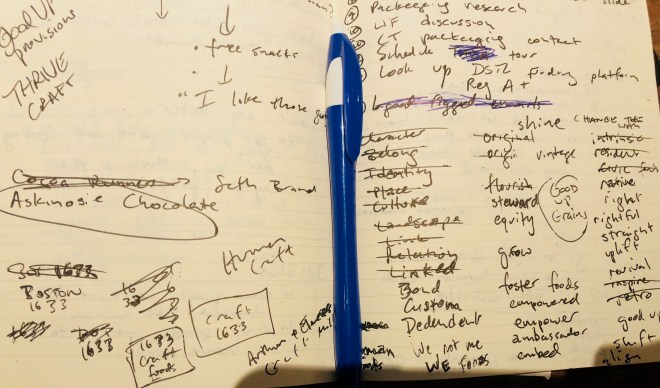

That’s Chris. He started a big digital marketing agency in Boston. We met a few years ago when his firm designed a mobile app for my last company. So, after more deliberating, we came up with these 2 finalists:

So, after more deliberating, we came up with these 2 finalists: This needs a name. This really needs a name.

This needs a name. This really needs a name. Since this will be my second crack at building a company, I know there’s something we need to do in order to have the chance to build a great, authentic brand, instill a culture that inspires team members and customers, and be an effective leader.

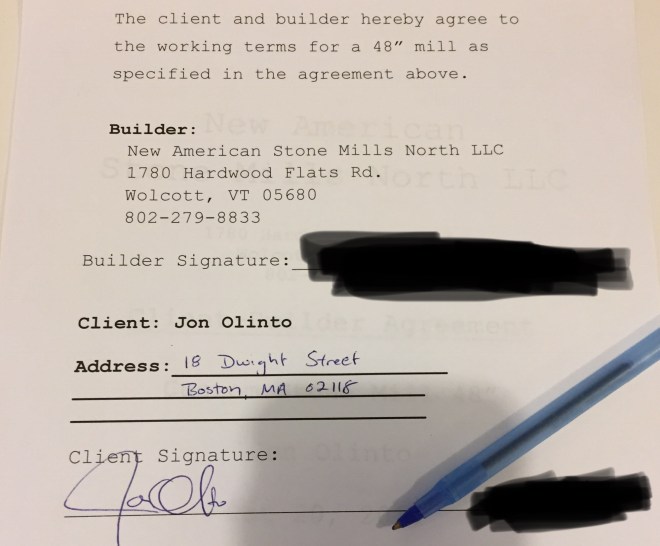

Since this will be my second crack at building a company, I know there’s something we need to do in order to have the chance to build a great, authentic brand, instill a culture that inspires team members and customers, and be an effective leader. The check is cut. So, we bought a mill. Well, we kind of bought a mill. What we definitely did do is sign an agreement to buy one and send a check for the deposit.

The check is cut. So, we bought a mill. Well, we kind of bought a mill. What we definitely did do is sign an agreement to buy one and send a check for the deposit. A few months ago, there’s no way I’d have ever believed that I could be so happy about sticking my hand in a bucket of flour. And I’d never have believed that I’d be happy about driving to the far corners of New England to pick up wheat berries in Maine and mill them in Vermont.

A few months ago, there’s no way I’d have ever believed that I could be so happy about sticking my hand in a bucket of flour. And I’d never have believed that I’d be happy about driving to the far corners of New England to pick up wheat berries in Maine and mill them in Vermont.

I play old-man basketball every Thursday night. After hoops, we hit a local pub for post-game beer and camaraderie. Among the over-the-hill ballers is Oscar, Head of School for an urban high school in Boston that serves inner-city kids. This Thursday, I was discussing my business concept with Oscar. Given his work as an educator and advocate for underserved kids and families, I wanted his thoughts on making a real impact.

I play old-man basketball every Thursday night. After hoops, we hit a local pub for post-game beer and camaraderie. Among the over-the-hill ballers is Oscar, Head of School for an urban high school in Boston that serves inner-city kids. This Thursday, I was discussing my business concept with Oscar. Given his work as an educator and advocate for underserved kids and families, I wanted his thoughts on making a real impact. Getting those brown bags in the back of my car was a really big moment.

Getting those brown bags in the back of my car was a really big moment. This was the day when my wife officially thought I lost my mind.

This was the day when my wife officially thought I lost my mind. Sorry for the extreme close-up. That’s me. I’m on a grain farm in Linneus, Maine.

Sorry for the extreme close-up. That’s me. I’m on a grain farm in Linneus, Maine.